The Buzz on Kentucky's Native Bees

By Katie Cody, Office of Kentucky Nature Preserves

Our native plants need native pollinators; they support nearly 90% of the world’s flowering plant reproduction. This pollination is mainly carried out by insects.

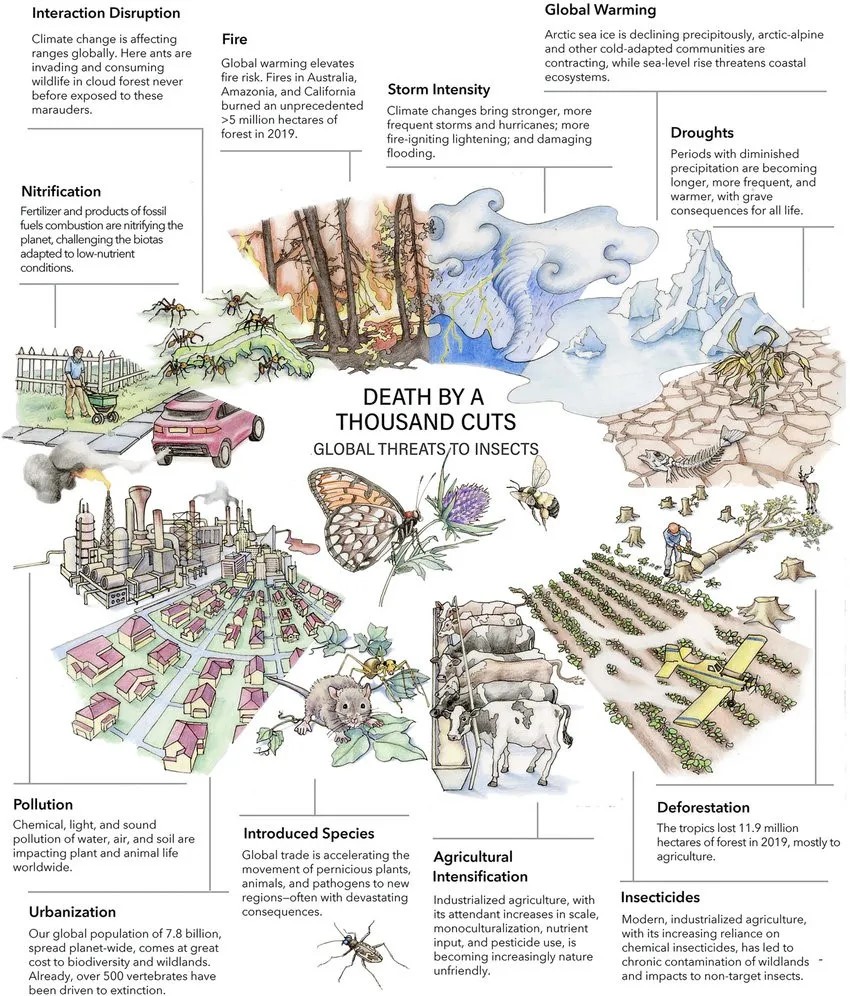

Pollinators are considered a keystone species because they are the glue that holds an ecosystem together; without these species, the ecosystem could collapse. In this way, pollinators are helping maintain the structure and function of our natural communities. Given their importance, the alarm has recently been sounded on their decline, which is happening worldwide. These declines are being driven by many factors, such as climate change, introduced species, agricultural intensification, land use change, and pesticide use, among others.

Of the pollinating insects, bees are the star of the show. But when many people think about bees, their minds may immediately go to the European honey bee (Apis mellifera). However, when we talk about our native bees, it isn’t fair to include this species — there are no honey bees native to the United States.

Honey bees are a predominantly managed species and have vastly different life histories than most of our native bees.

It’s important to also acknowledge that honey bees can negatively impact our native bees by outcompeting them for forage foods, decreasing their forage rates. They can even exacerbate the spread of invasive plants, which can distract our native bees from our native plants. Our native flowering plants and diverse natural areas depend on native bee visitation and diverse native pollinators to persist, not honey bees.

Native bee diversity and botany

Native bees are the most significant pollinator of flowering plants, and they are incredibly diverse. There are over 20,000 species found worldwide, and they occur on every continent except Antarctica. In the United States, there are around 4,000 species. Kentucky’s current state list of bees contains just under 200 species. Our native bees come in all shapes, colors, and sizes. They range from the extremely small, just a few millimeters, up to an inch or more. They come in brilliant blues, metallic greens, and bright yellows. They can be fuzzy and fluffy, hairless and bumpy, and everything in between. All these spectacular species have the incredibly important job of pollinating our native plants.

Native bees have evolved to be extremely effective pollinators. Bees are the only pollinators that will actively gather pollen and move it across the landscape (with a few exceptions in the wasp world). Other pollinator groups, such as beetles, flies, wasps, butterflies, and moths, will visit flowers to drink nectar or consume pollen, but don’t intentionally move pollen around.

Microscope views of Halictus ligatus (left) and Megachile petulans (right) showing the large amount of pollen bees can collect in their “hairs”; Photo credit: Katie Cody, Office of Kentucky Nature Preserves

Bees have evolved specialized morphology for gathering and carrying pollen. Their bodies are covered in hairs and parts of their body will be thick with specific pollen-carrying hairs called “scopa.” Scopa are usually dense on one part of the body, such as the legs or underside of the abdomen and are highly branched.

Some bees, such as the bumble bees, also have “corbicula” or “pollen baskets,” which are wide, smooth areas on their hindlegs surrounded by a dense fringe of hair to hold large loads of pollen. This is why you see bumble bees flying around with large orange balls on their back legs. Beyond morphology, bees also have flower constancy — they will repeatedly visit the same flower species on a foraging trip, making them very effective pollinators.

Native bees also have unique life history strategies. Very few are eusocial like the European honey bee, meaning that they have a social organization, a single queen producing offspring, cooperative brood care, and a division of labor. One of the few groups of native bees that are eusocial are our bumble bees, of which there are around 12 documented native species. The vast majority (over 90%) of our native bees are solitary and the female has her own nest that she cares for.

Most native bees (around 70%) are also ground nesters and will excavate bare soil to create their nests. The other 30% nest in dead stems, woody debris, abandoned rodent burrows, or other cavities.

Despite all we know about these incredible pollinators, there is still much to learn. Native bees are severely understudied and there’s a substantial gap in our knowledge of the diversity and distribution of Kentucky’s species. In light of their declines, it’s more important than ever to document, monitor, and manage their persistence.

The Office of Kentucky Nature Preserves (OKNP) recently established the Kentucky Native Bee Inventory and Monitoring Program to document and assess the conservation status of our native bees across the state. And you can help too! Native bees and native plants need each other to thrive, so planting a diversity of native plants with blooming times throughout the year can provide forage for most species. If you’d like to go a step further, you can provide nesting habitat by leaving last year’s pithy stems, areas of bare soil, and fallen woody debris near your flowering plants. You can also join in on OKNP’s monitoring efforts by snapping photos of any bee observations and uploading them to iNaturalist! These observations will be added to data collected by OKNP’s monitoring program to assess the rarity of bees across Kentucky. To stay up to date on our monitoring program, be sure to follow us on Facebook for updates and exciting finds!

Graphic credit: Virginia R. Wagner, 2021 in: Wagner DL, Grames EM, Forister ML, Stopak D. 2021. Insect decline in the Anthropocene: Death by a thousand cuts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 118(2): e2023989118